Following up on our 2024 Trial Statistics Trends at the PTAB, this blog post expands on the statistics and trends at the PTAB for the Fiscal Year 2025 (“FY25”), which runs from October 1, 2024 through September 30, 2025.

Petitions Filed

In FY25, 1,433 petitions were filed, which was 145 petitions more than the petitions filed in FY24.[1] Out of the 1,433 petitions filed, 95% were for inter partes review (“IPR”) and 5% were for post grant review (“PGR”).[2] In comparison to FY24, the percentage of petitions filed in each technology remained consistent. Specifically, 67% of petitions were electrical/computer (compared to 69% in FY24), 20% mechanical or business methods (compared to 22% in FY24), 7% bio or pharma (compared to 6% in FY24), 6% chemical (compared to 3% in FY24), and less than 0.5% design (compared to less than 1% in FY24).[3] Accordingly, in terms of the number and technology fields for petitions filed, FY25 was consistent with prior fiscal years at the PTAB.[4]

Institution Rates

Unlike the consistency with the petitions filed, FY25 revealed significant differences in the institution rate trends. As a result of the changes described in the numerous memoranda issued by the PTAB over the past year, the PTAB split the disposition rates into Director Discretionary Considerations (“DSCO”) and Board Disposition Decisions.[5] For DSCO, the director denied institution for 304 petitions (60%) and referred 201 petitions (40%) to the Board.[6] Thus, out of 935 total petitions, the Board granted institution for 66% (620 petitions) and denied institution for 34% (315 petitions).[7] In combination, this resulted in an institution rate of 50% for FY25 based on the 620 petitions that were granted institution and the 619 petitions that were denied institution either by the Director or the Board.[8]

Outcomes

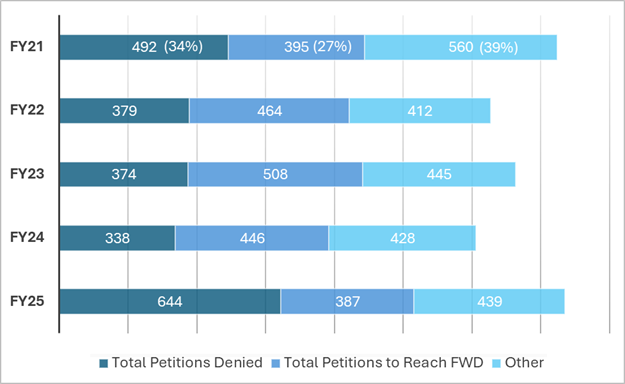

In FY25, 1,470 petitions reached an outcome at the PTAB between October 1, 2024 and September 30, 2025. Out of the total petitions, approximately 26% (387 petitions) reached final written decisions. Out of those that reached final written decisions, 17% (250 petitions) held all claims unpatentable, 4% (62 petitions) held all claims patentable, and 5% (75 petitions) held some claims patentable and some claims unpatentable. Additionally, 44% (644 petitions) were denied institution either by the Board or DSCO. For the remaining petitions, 25% (368 petitions) settled, 2% (36 petitions) requested adverse judgment, and 2% (35 petitions) were dismissed.[9]

Source: The data for this chart can be found at https://www.uspto.gov/patents/ptab/statistics

As shown by the chart above, the percentage of petitions denied institution in FY25 increased by at least 10% over the last five years, while the percentage of petitions to reach final written decisions decreased by at least 10%. Notably, the number of petitions to request adverse judgment, settle, or be dismissed remained relatively consistent, which indicates that this category of outcomes did not impact the institution rate.

Conclusion

The FY25 PTAB trends, specifically regarding the decrease in institution rates, reflect the changes that patent practitioners have monitored throughout the past year. As changes to the framework for discretionary denials continue, it is likely that institution rates will continue to decrease even more significantly than the 10% decrease reflected in FY25. Thus, it remains of important for PTAB practitioners to continue to monitor PTAB guidance and statistical trends to provide the best representation for their clients by considering alternative strategies and assessing risk.

More information about the PTAB’s trial statistics for FY25 and previous years may be found at: https://www.uspto.gov/patents/ptab/statistics.

[1] See PTAB Trial Statistics FY25 End of Year Outcome Roundup IPR, PGR, USPTO, 3 https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Trial_StatsFY25_Q4.pdf (last visited Dec. 20, 2024); see also PTAB Trial Statistics FY24 End of Year Outcome Roundup IPR, PGR, USPTO, 3 https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ptab_aia_fy2024__roundup.pdf (last visited Dec. 20, 2024)

[2] See PTAB Trial Statistics FY25 at 3.

[3] See id.

[4] See https://www.ptablaw.com/2025/01/06/trial-statistics-trends-at-the-ptab-2024-edition/

[5] See PTAB Trial Statistics FY25 at 6.

[6] See id.

[7] See id.

[8] See id. at 7.

[9] See id. at 11.